Cooking and deckbuilding shouldn’t fit together, but A la Card makes the pairing feel obvious. Shook Loose turns ingredients into cards, recipes into combos, and the serving window into a tight little puzzle where order matters and wild mutations can flip your plan in an instant. The team chases the fun of “breaking” a run without letting any one card solve the game, and they’ve rebuilt core systems to make that depth easier to learn.

In this interview, SoBad and Ash talk about tuning outrageous synergies, designing bosses that test your build without hard counters, and why onboarding exposed a bigger design choice than any tutorial could. We also get into trinkets, mid-run edits, the Unity toolchain they rely on, and Josh Whelchel’s score that ramps up as your kitchen heats up. A la Card is heading toward launch with hundreds of cards, a pile of trinkets, and the kind of discovery that keeps roguelike fans coming back for “just one more meal.”

What was the original spark for mixing cooking with deckbuilding, and how did that idea evolve from prototype to what we see now?

Cooking is very piecewise. You can take a bit of this and that and adapt based on what you have on hand, which is exactly how A la Card works! Food also naturally lends itself to categories, so very little effort is required to think up distinctions between different types of cards. Want colors? Use food groups!

Each ingredient card has a unique effect you can use to make interesting plays, just like how every ingredient brings its own unique flavors to the pot.

We lean into the framing device as much as possible. The familiarity makes it easier to communicate the design, and you don’t have to learn 300 fantasy character names!

The Steam page mentions wild card mutations and “absurd synergies.” What’s an example of a combo that went from broken to balanced during playtesting, and how did you tune it?

The most fun thing you can do in A la Card is discover something completely broken. Whether something is too broken is centered around that discovery: How hard is it to break? How hard was it for the player to figure that out?

Uncovering a crazy synergy makes you feel smart and accomplished and excited to call your parents, but stumbling onto a single card that wins the run for you is boring. During the card design process, the only question we allow each other to ask is, “Without ANY mutation, is this card broken?” If the answer is no, we’re in the clear.

One example of something we try to watch the power level of closely is cards that clone themselves, since they can sort of be the whole machine on their own.

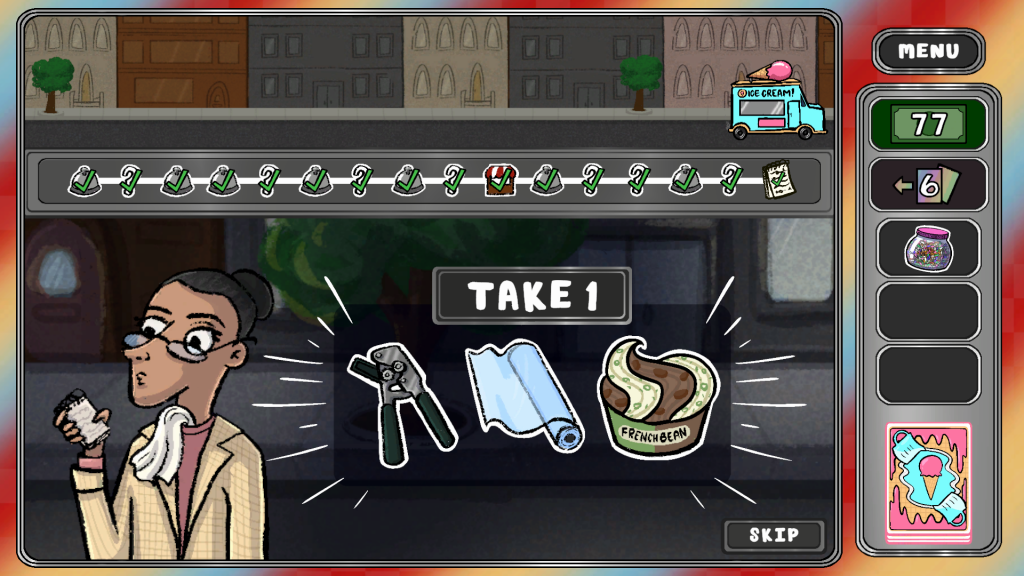

We’ve rebalanced almost everything continually while sharpening the systems and mechanics. There was a trigger in the first demo that would go off when ANY other card was played, up to 15+ times per round if you were maximizing it. We’ve adjusted it so it only goes off when another food is prepared, which limits the number of triggers to the spaces available in the window (6 or fewer, unless you discover a different way to break it). It’s a slight adjustment that still lets you scale like crazy, but it’s not a surefire way to win the game.

How do the “sequence your cards” mechanics shape moment-to-moment decisions? Any lessons you learned about teaching sequencing without a long tutorial?

When the order of the cards matters, it introduces a second arm of gameplay and decision-making beyond the deckbuilding. There’s no way to build a deck that will win for you. Every ingredient you pick up is like a flexible puzzle piece that you get to work into your solution.

A friend of ours described his experience with the card-play sections of the game like “trying to find lethal in Hearthstone,” and we think that really does capture the agency the player has over stealing a win from (into?) the jaws of hungry customers.

It’s a dense game, so we’ve done our best to keep the tutorialization as short as possible. We have a few sentences at key moments instead of a dedicated tutorial level. No one wants to sit through a tutorial anyway! Doing (and failing) is the best way to learn, so prepare to upset a few customers along the way.

Bosses act like small puzzles. How did you design them so they test flexibility without hard-countering certain decks?

We’ve drawn a lot of inspiration from lots of games, but we love how Balatro’s bosses can throw a wrench in your build. We’ve structured our levels so that every boss is designed to test a specific weakness, and some customers that come before the boss have a similar effect as a forewarning to what’s coming. You’ll have lots of time to adapt!

One of our favorite levels is Biff’s Cliffs and Rapids (a beaver-themed water park, if you haven’t made plans for next summer). There, some customers take away a precious window space by vomiting into it. It’s very gross, and you’ll feel motivated to come up with a solution. Once you get to Biff at the end of the level, he beavers it up and jams the window with logs. If you prepared a counter for the customers, you should be equipped for the boss fight too!

Our ultimate goal with our boss design is to highlight the strengths that benefit all decks, like being able to manage space in the window, without forcing any deck to be generally flexible.

Trinkets seem to define starting decks. What design rules do you use to keep trinkets powerful but not prescriptive?

Trinkets are definitely designed to be powerful, but they’re also meant to be a divining rod for a general build direction.

For example, the Burger deck has Protein Powder as the starter trinket, which gives all your red cards a +1 boost. With this deck, you’ll have a stronger preference for taking red cards than you normally would, which results in the player being willing to try certain cards they might otherwise undervalue. For contrast, the starter trinket for the Sushi deck turns your recipes into a draw engine, which incentivizes the player to support a larger number of recipes in their build.

Because you can hold six trinkets, there are lots of ways to expand into different paths. The trinket offered is intended to be built upon with lots of other trinkets, techniques, and skillfully built plays designed by the players themselves.

From a design perspective, there’s a bonus to making the most powerful objects in the game extremely niche: it balances them. If you’re offered something insanely powerful, there needs to be a reason to turn it down. Being able to make the right choice (and occasionally, the wrong choice) is an important part of that feel-good discovery process.

Random events let players swap colors, stats, and triggers. Where did you draw the line on how much mid-run editing is too much?

This is a conversation we’ve had in depth. The deckbuilding component of the game hinges on trying to nudge your deck in the right direction while it mutates more and more, and it’s definitely possible to fumble with the extent of this. We’ve actually found that we have competing philosophies:

SoBad, being bald but otherwise of sound mind and body, prefers only the smallest incremental changes at a time, the summation of which yields variety run to run. No two final decks could ever be identical because no two players will make the same 25 incremental changes in a row.

Ash worries that small changes feel less meaningful over time. Adding yellow to one of your thirty 3-color cards has way less impact than making your first 2-color card in a 5-card deck.

Ash prefers consistently significant change. As your deck mutates more and more, it requires a more drastic mutation to make player decisions interesting: big risks, big rewards (it’s worth noting that Ash doesn’t have to program any of it).

SoBad worries that too-large changes can cause deck designs to converge. A late-game event that makes every card in your deck yellow would cause different players to frequently end their runs with all-yellow decks.

Where we agree is that card-mutation events are only fun if the player feels like their choices are meaningful. There’s also less fun to be had if you have to win 3+ meals in a row using the exact same strategy every time. You already proved it works! Consistently weaving between meals (the card-playing portion) and mutation events (the deck or card-modifying portion) keeps your gears turning while still testing your decisions as often as possible. And gradually increasing the severity of the mutations offered keeps each change feeling impactful.

The soundtrack is called out on the page. How early did audio get involved, and did any track inspire a mechanic or encounter?

We have enough respect for the art form to have known very early on that we wanted an experienced composer to tie the game together rather than amateurishly try to make something ourselves. Josh was our first choice, and we can no longer imagine A la Card without his influence.

He brings such a spirited energy and willingness to help with whatever he can. It was his idea to design the tracks to seamlessly blend into more intense versions of themselves as the player progresses further into each area of their run, which honestly adds so much. We also think that without him, we wouldn’t have considered including vocals in one particular boss-intensity track to pair with a superstar songstress.

He’s a phenom and a pillar (and some sort of creativity fae creature). And you can check out his stuff here!

What are your goals for launch and beyond in terms of new cards, trinkets, or modes? How will you keep the meta fresh without power creep?

At launch, the game will have well over 200 cards and more than 50 trinkets.

For a stretch of time after release, we plan to frequently and consistently add more to keep injecting freshness into the game. Maybe even multiple times per week! We’re still having fun, so why stop?

The base game also has 8 starter decks, and we’re having discussions about how to add more, whether in the form of a special rotating deck, a bulk drop in a DLC, or some secret third thing even we don’t know about!

We’re not really concerned about potential power creep so long as new cards follow our existing design philosophy of requiring other cards or mutations to become truly broken.

Accessibility and approachability for deckbuilder newcomers can be tricky. What options or onboarding choices are you including so more players can enjoy the game?

Onboarding is the single most overlooked aspect of essentially any game we’ve ever found ourselves complaining about. It is crucial. Not only for the player’s experience, but also as a means for the developer to evaluate their game’s core design.

Sure, there’s low-hanging fruit like your tutorial being too long or too text heavy, or neglecting to explain anything at all. But higher up in the tree, some pompous lemurs are deep in conversation: “Your onboarding is a microcosm of your entire design paradigm.” If you squint your ears, you can hear faint murmurs of, “If you think you have an onboarding issue, it might actually be the case that you have a core game design issue.”

In early tests, we noticed the mana system in A la Card was unintuitive for new players, despite how simple we convinced ourselves it was. (Like, really, if you draw a red card, you get a red mana. Easy peasy, right?) We worked hard to improve the conveyance with sounds and animations. When that didn’t solve it, we added an explicit tutorial.

Then we watched streamers and playtesters continue to misunderstand or fail to even notice it. So we climbed a little higher up the tree, and what we learned from this failure of onboarding was that this mana system does not make sense in our game.

A “you can’t just play all your cards” limiting mechanic already exists via the small number of slots for foods. The mana system was double-dipping this limitation, and having two competing systems caused them to distract from each other during those pivotal first few minutes of onboarding, making both harder to learn. As a player, if you already notice a reason you can’t do something, would you go looking for another?

After removing the mana system, we were left with a game that’s easier to learn, and the potential for depth stays the same thanks to the already existing limiting mechanic.

From a development standpoint, what does your toolchain look like? Engine choice, key plugins, build pipeline, and any custom tools you built to design cards or events faster?

We use what we’re already familiar with: Unity, Procreate, and Git. Sling code in any text editor with a “go to definition” function (which is all of them).

Plugins-wise, KyryloKuzyk’s PrimeTween has been effortless to use, and it’s always nice to have a tweening library on hand. We also enjoyed having mackysoft’s SerializeReferenceExtensions save us some time when it came to making a codeless card-effect editor.

These are not recommendations, and we’re not in the habit of recommending tools since we wouldn’t want new game devs to think that tooling is something they need to worry about before they’ve already made several games.

What was the toughest production challenge so far, and what did it teach you about scoping a systems-heavy indie game?

The least romantic answer is probably the most accurate one: There is no tougher production challenge than having no budget for your game. You can find clever workarounds for essentially any other problem you’ll ever encounter, but there is no avoiding the reality that games take time and effort to make, on the span of years, and even if you never pay a cent for assets, external talent, or marketing, you burn money via the opportunity cost of spending all of your spare time sanding away at your craft.

Indie devs frequently find themselves making their games for “free” this way and with no guarantee of getting a tangible return. If you aren’t already spending your time making games as a hobby, don’t try to spend it making games as a career.

With regard to scoping a systems-heavy game, one obstacle is the fact that individual systems are likely irreducibly complex. If you decide late in development that you need to scope down, you either can’t, or you have to cut entire systems wholesale, which can mutate your game into a different experience entirely. Whereas in a game with fewer systems, larger portions of your experience might be made up of other content that is easier to cull. Consider a narrative that can have a character or subplot removed without suddenly becoming not a narrative, or a world map that could have extraneous areas trimmed very late in development.

Maybe it would be fair to say that new entrants to game development as a hobby should focus on systems-light games first, so they can enjoy the safety of that last-hour flexibility while they develop the skill set of scoping their projects effectively. Game jams are great for this. You’d be shocked by what you can make in two days, and even more shocked by what you can’t.

When can we start playing?

We’ll be launching before the end of the year, and you can wishlist A la Card on Steam to get notified the moment we do!

(Eagle-eared superfans might even notice the bush-rustling of a final pre-launch demo! Oooo!)

Follow-Up Questions

How did Shook Loose as a team come together?

We were each sharing updates on our solo-developed games in a Discord for game developers. Each of us thought the other’s solo project was really cool. We were meeting to work on our separate games, kind of as accountability partners.

After about a month or two of that, we’d finished up our solo games and tried a couple of game jams to test the waters. We ended up taking first place in Ludum Dare in the humor category (with a silly little game called Some Munnings, if you want to try it). We had so much fun with these game jams that it was easy to transition into bigger projects together.

Finally, our last question comes from zilard, developer of Raybounder, the previous game we highlighted here at SDC! They asked: What is the most memorable bug you encountered while working on your game?

We actually kept our favorite bug in the game! In A la Card, every level has a unique multicolor background behind the UI elements. It matches the colors of the zone’s environment. Technically, this color should reset when you end the level. As is, if you go back to the main menu, the background color doesn’t revert to the main menu color scheme; it keeps the zone colors.

We found it charming, so we decided to keep it that way.

What question would you like to ask the next SDC Highlight developer?

How do you balance the art you want to make with the product you want to sell?